The Real Story on Whole-House Surge Protection

Protecting your home from power surges has gotten complicated with all the products and conflicting advice flying around. As an electrician who’s seen surge damage ranging from fried TVs to completely cooked HVAC control boards, I learned everything there is to know about what actually protects homes versus what just makes people feel safer. Today, I’ll share it all with you.

Your house is full of expensive electronics now. Smart TVs, gaming consoles, computers, smart home gadgets, appliances with digital brains everywhere. Most homeowners think their power strips handle surge protection. They don’t. Not really. And the difference between what they think they have and what they actually need can cost thousands when a serious surge hits.

Where Surges Actually Come From

Electrical surges are brief voltage spikes above the normal 120 volts your outlets deliver. They come from more sources than most people realize, and understanding them helps you understand why protection at different points matters.

Outside Your Home

- Lightning: The dramatic one, though not the most common. Direct strikes can send 300 million volts through your system. Even strikes a mile away induce surges in power lines. The Pacific Northwest sees its share of storms, especially in certain seasons.

- Utility switching: Power company grid and transformer switches create voltage fluctuations. Happens more often than you’d think, especially during high-demand periods.

- Downed power lines: Lines contacting each other or trees send irregularities through the grid. Wind events in the Northwest cause plenty of these.

- Industrial neighbors: Big motors at nearby businesses create surges every time they cycle on and off. If you live near commercial or industrial areas, this affects you more.

Inside Your Home

Probably should have led with this section, honestly — up to 80% of surges start inside your own house. Every motor-driven appliance creates small voltage spikes when cycling:

- HVAC compressors

- Refrigerators and freezers

- Washing machines and dryers

- Garage door openers

- Power tools

- Hair dryers and vacuums

Each surge is tiny — maybe a few hundred volts for microseconds. But they accumulate over months and years. This “electronic rust” gradually degrades the microprocessors in everything you own, shortening device life and causing weird intermittent failures that are impossible to diagnose. Your TV that dies after three years instead of ten? Internal surge damage is often the culprit.

Why Power Strips Don’t Cut It

That’s what makes surge protection endearing to marketing departments — they can slap “surge protector” on a power strip and charge extra for what amounts to basic protection. But there are real limitations that matter:

Joule Ratings Run Out

Surge protectors have joule ratings — the total surge energy they absorb before they’re toast. Most consumer strips offer 200-1,000 joules of protection. A serious surge from nearby lightning carries tens of thousands of joules. Once a protector hits its rated capacity, it’s done protecting — permanently. Usually with no indication it failed. You might be using a “surge protector” that’s been a regular power strip for years without knowing it.

Only Protects What’s Plugged In

Power strips only cover devices plugged directly into them. Your hardwired appliances — HVAC system, electric water heater, built-in microwave, dishwasher — have zero protection. Neither does anything plugged into unprotected outlets elsewhere in your house. It’s a patchwork defense at best.

Service Entrance Is Unprotected

Surges enter through your service entrance before spreading throughout your home. By the time one reaches your power strip, it’s already traveled through your entire electrical system, potentially frying anything in its path. Protecting endpoints while leaving the entrance wide open defeats the purpose.

How Whole-House Protection Actually Works

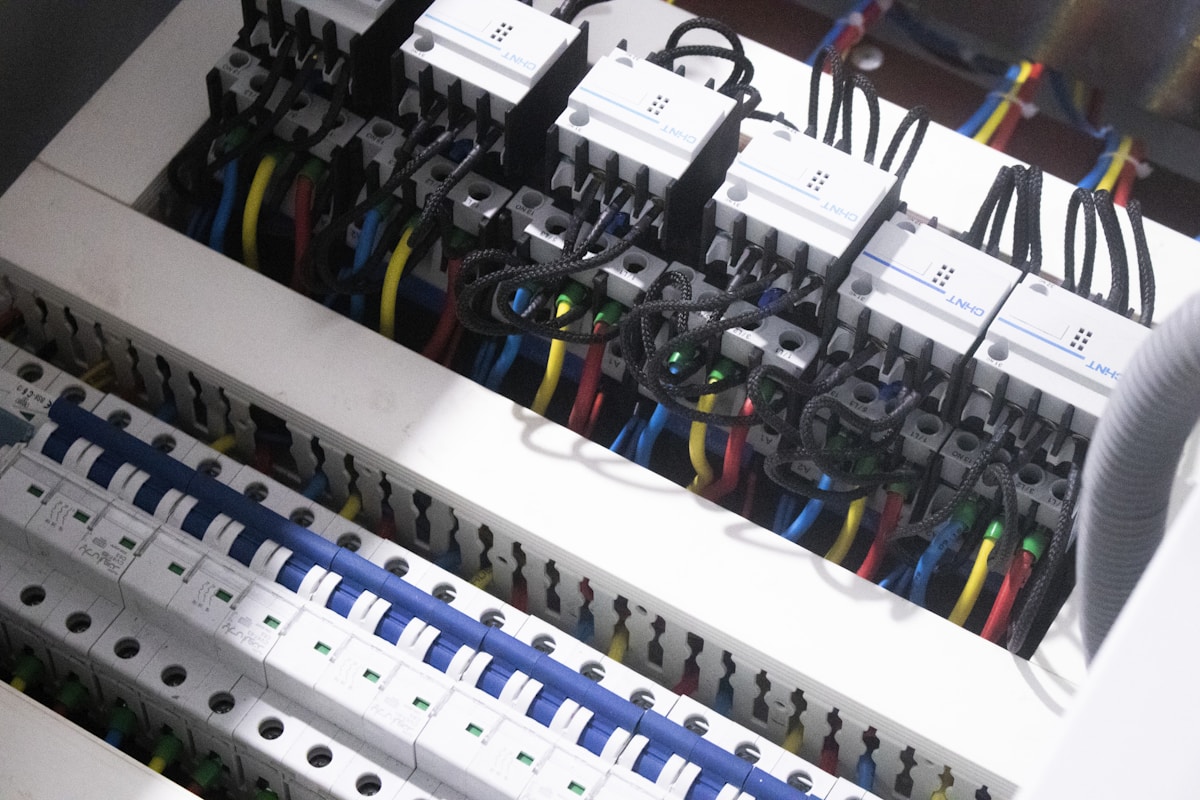

Whole-house surge protective devices (SPDs) install at or near your main panel, catching surges before they get into your home’s wiring. They use metal oxide varistors (MOVs) that work like voltage-sensitive switches:

- At normal voltages, MOVs resist current and let electricity flow normally to your circuits

- When voltage spikes, MOVs instantly become conductive and shunt excess voltage safely to ground

- Once voltage normalizes, MOVs go back to high resistance and normal operation resumes

This switching happens in nanoseconds — fast enough to protect sensitive electronics from the spike before damage occurs.

Type 1 vs. Type 2 SPDs

Type 1 installs before the main panel, usually at the meter or service entrance. This is your first line of defense against external surges coming in from the utility side.

Type 2 installs at the main panel or subpanels, protecting against internal surges and anything that gets past Type 1 protection.

Many electricians recommend both types for comprehensive coverage, though Type 2 alone provides significant benefit at lower cost if budget is a concern. Something is much better than nothing.

Installation Realities

Don’t DIY This

SPD installation means working inside your main panel with live 240-volt circuits. Licensed electricians have the training, equipment, and insurance for this work. Most installs take 1-2 hours and can piggyback on other electrical work you’re having done, saving you money on the service call.

Grounding Makes or Breaks It

Surge protection only works with proper grounding. SPDs divert excess voltage to ground — bad grounding means the surge has nowhere to go and protection fails. Your electrician checks grounding before installation and recommends upgrades if needed. This is non-negotiable for effective protection.

Warranties Require Proof

Quality SPDs include connected equipment warranties — manufacturers promise to pay for damage if the SPD fails to protect. These typically require professional installation and documentation. Keep receipts and registration info in case you ever need to make a claim.

The Math Works Out

Whole-house SPD costs $200-500 installed depending on device quality and panel configuration. Compare that to potential losses from a single surge event:

- Smart TV: $500-2,000

- Gaming console: $300-600

- Desktop computer: $500-3,000

- Smart home hub and devices: $200-1,000

- HVAC control board: $300-800

- Refrigerator control board: $200-500

- Washer/dryer electronics: $200-600

One surge event can easily cost more than a decade of whole-house protection. The economics aren’t even close. Most homeowners spending $300 on protection are protecting $5,000-20,000 worth of vulnerable electronics.

The Layered Approach

Power strips still serve a purpose — they’re fine for cable management and providing extra outlets where your whole-house surge protector coverage already exists. Think of them as secondary protection for your most sensitive gear. But relying on them as your main and only defense? That’s leaving thousands of dollars in electronics exposed to damage that costs a few hundred to prevent.

Whole-house protection at the panel catches most surges before they spread. Point-of-use strips at computers and entertainment centers provide an extra layer. Together they create defense in depth that actually protects your investment in modern home electronics.